Landor, The Word “Dear” on the Upper Verge

By Robert Pinsky

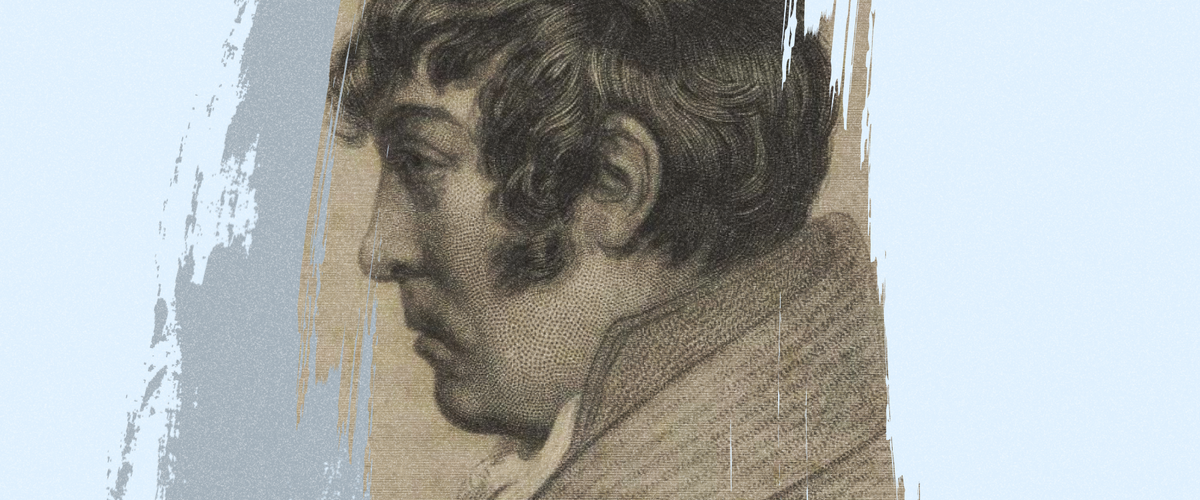

We who are getting older— everyone is, but the term accumulates force with time— have particular reasons to consider Walter Savage Landor (1775-1864). Note those dates. A memorable sketch of him shows him reading Homer, which he decided, since he had lived so long, to read, in the original Greek, one more time.

Landor kept writing into his nineties. In his late seventies he published a book called Last Fruit Off an Old Tree expecting it to be his last. Five years later he published another book, titled Dry Sticks. As those titles suggest, he could be funny about the subject. One poem begins, “The leaves are falling; so am I.”

Landor’s poem “Memory” was teasing in my own memory when, in this Forum a couple of months ago, I introduced Elise Partridge’s poem “Chemo Side Effects: Memory.” Landor was deeply literary, a writer when that word’s meaning included someone who made marks on paper, by hand. That action of applying ink to paper inspires the memorable, heartbreaking moment in his poem. When he sets out to write a letter to a friend, the word “Dear” “hangs on the upper verge,” waiting for the unremembered name. The conventional word of the salutation (in email, largely supplanted by “Hi”) takes on a great charge of feeling: the attachment to the person and the passion to write, momentarily survive the ability to remember the name.

For some contemporary readers may Landor’s language may seem merely old-fashioned, with its lofty, Latinate “vernal” and “autumnal” for spring and fall; personally, I am all the more moved by the formal, somewhat learned language: the implicitly classically trained mind expressing its attachment to the seasons, as to friends, to writing, to the one beloved he remembers best. For that great love of his life, Jane Swift, he invented the name “Ianthe” in his many poems to and about her.

It’s impressive to me that Landor can put that love-ideal in the context of other relationships, including his ability to write, or to remember. Early friendships and more recent ones, he says, are equally vulnerable to oblivion. For me, this nineteenth-century poem by someone who felt old so long ago, gets sharper as the language itself— along with us all— keeps getting older, and changing.

MEMORY

The mother of the Muses, we are taught,

Is Memory: she has left me; they remain,

And shake my shoulder, urging me to sing

About the summer days, my loves of old.

Alas! alas! is all I can reply.

Memory has left with me that name alone,

Harmonious name, which other bards may sing,

But her bright image in my darkest hour

Comes back, in vain comes back, called or uncalled.

Forgotten are the names of visitors

Ready to press my hand but yesterday;

Forgotten are the names of earlier friends

Whose genial converse and glad countenance

Are fresh as ever to mine ear and eye;

To these, when I have written, and besought

Remembrance of me, the word Dear alone

Hangs on the upper verge, and waits in vain.

A blessing wert thou, O oblivion,

If thy stream carried only weeds away,

But vernal and autumnal flowers alike

It hurries down to wither on the strand.

Originally published in the Robert Pinsky Poetry Forum, September 17, 2014.