The Sweetest Dream that Labor Knows: Williams and Frost

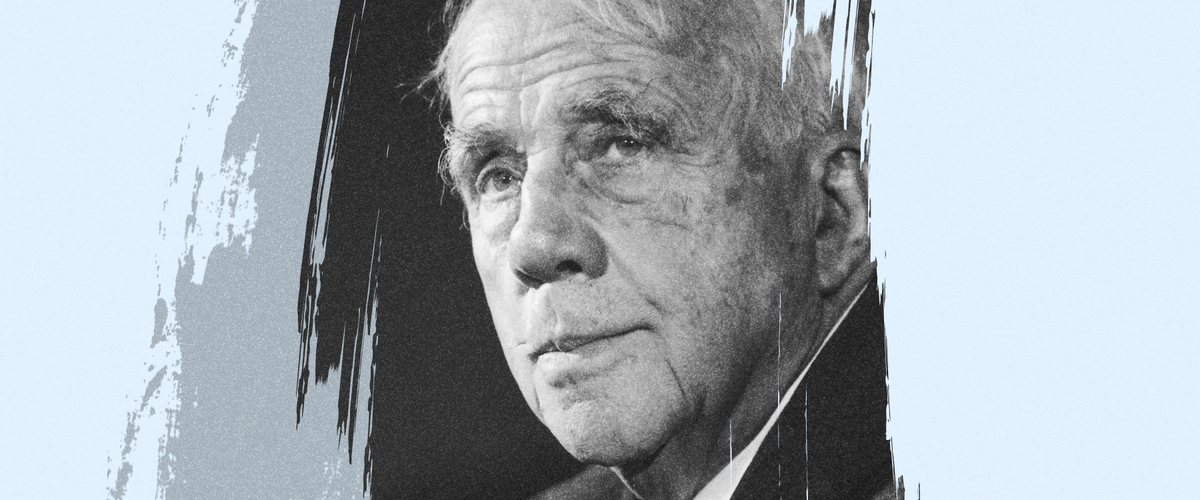

By Robert Pinsky

The poetry of William Carlos Williams and the poetry of Robert Frost are more similar, in spirit and practice, than conventional ideas about them might convey.

As examples of what I mean, here are two poems about work. Mowing and roofing, in these poems, have implications for the work of writing, but in both poems the physical labor itself is also respected, in attentive detail. “The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows,” says Frost, summarizing one element in American modernism: attention to the hard edges and exact textures of reality, in reaction against a merely dreamy or idealized, poetic vision. “It was no dream of the gift of idle hours,/ Or easy gold at the hand of fay or elf.”

Williams, too, writes with an “earnest love.” If “anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak,” then a beautiful, deadpan sentence about eight foot strips of copper, beaten lengthwise at right angles, can dance across two stanzas.

“It was a time,” says Williams in I Wanted to Write a Poem, “when I was working hard for order, searching for a form for the stanzas, making them little units, regular, orderly. The poem “Fine Work with Pitch and Copper” is really telling about my struggle with verse.”

Like Marianne Moore writing about “The Master Tailor” with his “invisibly executed pockets” and “buttons of ocean pearl—no two alike,” these poets look at the tools and materials of work with implicit attention to the craft of verse. Frost’s unconventionally rhymed sonnet and Williams’ neat triads, both, are means toward a goal of lucid attention to materials and tools. Both poems listen to what the work whispers. Both take up the material and run an eye along it, while ruminating, both, with a feel for American idiom.

FINE WORK WITH PITCH AND COPPER

Now they are resting

in the fleckless light

separately in unison

like the sacks

of sifted stone stacked

regularly by twos

about the flat roof

ready after lunch

to be opened and strewn

The copper in eight

foot strips has been

beaten lengthwise

down the center at right

angles and lies ready

to edge the coping

One still chewing

picks up a copper strip

and runs his eye along it.

MOWING

There was never a sound beside the wood but one,

And that was my long scythe whispering to the ground.

What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself;

Perhaps it was something about the heat of the sun,

Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound–

And that was why it whispered and did not speak.

It was no dream of the gift of idle hours,

Or easy gold at the hand of fay or elf:

Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak

To the earnest love that laid the swale in rows,

Not without feeble-pointed spikes of flowers

(Pale orchises), and scared a bright green snake.

The fact is the sweetest dream that labour knows.

My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make.

Originally published in the Robert Pinsky Poetry Forum, February 12, 2014.