The example of singing or reciting to an infant has a lot to do with the connection between poetry and music. Another afternoon, caring for Benjamin, I followed the customary, maybe intuitive, pattern: I sang to him, as I had sung to babies a thousand times before.

But this one time, I also recited to the baby—first nursery rhymes, then Dickinson, Frost, Yeats—and I felt that the baby responded with the same signs of pleasure to the reciting as he did to the singing.

I experimented with some free verse (Elizabeth Bishop, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens) interspersed with songs. The baby appeared to like it all, without registering any difference between them. When I fell silent, he fussed gently, seeming to ask for more.

This is a really small sample, in a couple of senses. But my anecdotal evidence about singing and reciting poetry to my infant grandson has plenty of historical background. The very word “lyric” in “lyric poetry” refers to a stringed instrument, held in the hands, to accompany the voice. (Alcibiades, the Athenian aristocrat, scoundrel, warrior and pretty boy, is quoted by Plutarch as saying that a gentleman could play a lyre, but only slaves should play wind instruments, because they require distorting one’s face.) In the 1500s, at the beginnings of poetry in English, many poems were also songs. Thomas Campion (1567–1620), who wrote “Now Winter Nights Enlarge,” was a composer as well as a poet. The composer John Dowland (1563–1626) may or may not have written the words for his songs, such as “Fine Knacks for Ladies.” Sometimes a very good poem is also a very good song, as those works by Campion and Dowland demonstrate.

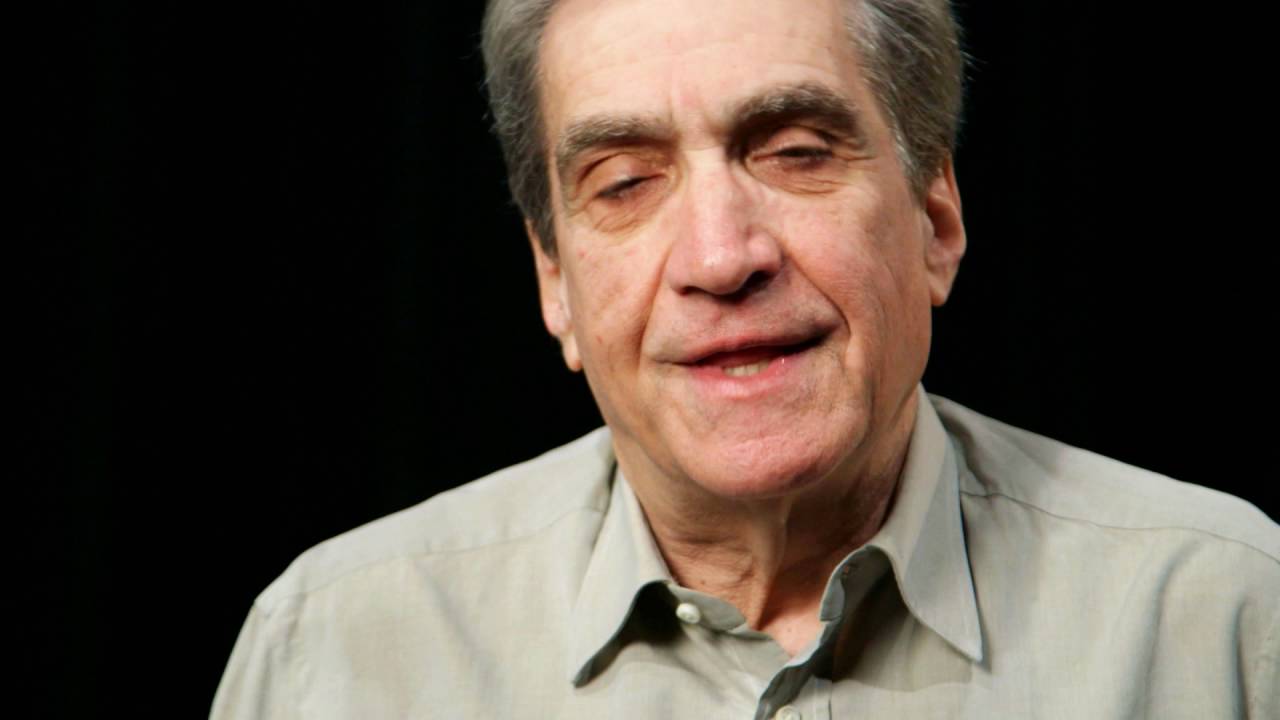

—RP